Cymdeithas Hanes Mechell

The Demography of Llanfechell 1851 & 1901

William Bulkeley and the poor of Llanfechell

Llanfechell in the early 19th Century

with thanks to Robin Grove-

Click on all photographs to see larger versions

In November 1732, at the age of 20, he married Martha Painter and had three daughters by her, including Phillipa who later married the grandson of the diarist, John Evelyn. Martha died a just a few years later.

In November 1736, at the age of 24, he married Mary Bulkeley, who was already pregnant with his child.

*********************************

What we have learnt about Fortunatus Wright from the Bulkeley Diaries

So who was Fortunatus Wright – and how did he become a privateer?

William Bulkeley’s Diaries: 1734 – 43 & 1747 -

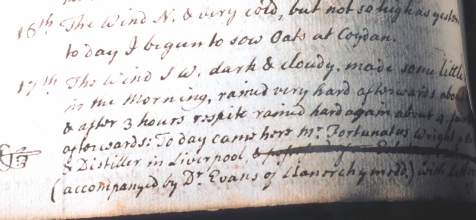

17th March 1738

Blanked out text from the diary

Today came here Mr Fortunatus Wright, a Brewer and Distiller of Liverpool, and possessed of an Estate of 120 a year accompanied by Dr Evans of Llanerchymedd, with letters of recommendation from Mr Wm Parry of Dublin, & another from my daughter Mary Bulkeley, whose suitor he has been these several years, she recommends him worthy of her love and esteem, who having … indiscretions … age and misfortune continued the same to show affection for her and desired my consent to have him for her husband, and tho I thought him not equal to her in Birth and that she might be vastly superior to him in fortune, yet considering her fired resolution to go with him, & also his sincere generous love for her, I then yielded to their desires. This gentleman since his departure from his boyous age married one Painter of Pembrokeshire a Cousin of his & has by her now 3 daughters who are (and appear…ed, that his Estate is not settled) to inherit his real Estate left his Daughters by his sd wife, but if he hath surety he & they want back place, his wife dyed in November last & took the first opportunity that he decently could to make a purpose voyage to Dublin to wait upon his old and first love & … this night, & till 5 o’clock next day. I shal expect him and my Daughter here from Dublin in 8 or 9 days time.’

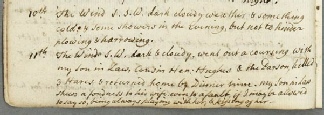

Diary entry for 11th April 1738

Went out a coursing with my son in law, cousin Henry Hughes & the parson, killed three hares and returned home by dinner time. My son in law shows a fondness to his wife, even to a fault, if I may be allowed to say so, being always playing with her, & kissing of her.’

***********************************

But what was a privateer?

It is important to stress the difference between a pirate and a privateer.

A pirate is someone who commits a warlike act (especially robbery or criminal violence at sea) but who is not affiliated with any government.

A privateer has a licence (called a Letter of Marque) granted by his government, giving him authority to attack enemy shipping and interrupt enemy trade. Strictly speaking this only happened during times of war, but in effect a privateer was a private warship. The costs of building and fitting out the privateers were borne by investors, who hoped to gain a significant return from prize money earned from the captured enemy (merchant) shipping. The captures had to be adjudicated by an Admiralty court, which decided whether or not they were ‘fair and legal prize’. If they were, the vessels and cargos would be sold at auction and the proceeds distributed amongst the privateer’s owners, officers and crew.

An example of Wright’s loot – 1680’s French miniature of an unknown Versailles courtier

The crew of a privateer were given immunity to the press (press gang) and a share of the prizes. If captured they were usually treated as prisoners of war and were often traded with enemy prisoners in prisoner exchanges. For some men it was an exciting opportunity for a taste of adventure.

For governments it was a cheap way of mobilising armed ships and sailors without spending public money! The privateers were of great benefit because they disrupted commerce and forced the enemy to deploy warships to protect merchant trade.

The goal of privateering was to capture ships rather than sink them – and it has

been argued that this is a less destructive and wasteful form of warfare. Many people

looked upon privateering as a state-

Captain William Hutchinson (himself a colourful and experienced privateer who sailed

with Fortunatus Wright and later became Dock Master at Liverpool) wrote of privateers

that “the captain was always some brave, daring man who had fought his way to his

position. The officers were selected for the same qualities: and the men – what

a reckless, dreadnought, dare-

Hutchinson, who wrote a famous book ‘Treatise on Practical Seamanship’ – speaks with evident pride of having served under Fortunatus Wright, and frequently refers to the practices of ‘that great, that worthy hero’ as illustrating different points of seamanship. (More of this later)

Gomer Williams (History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque) writes of FW: ‘He strikes the imagination as the ideal and victorious captain’.

Tobias Smollett in his book ‘History of England’ refers to FW as having ‘distinguished himself uncommon vigilance and valour’.

**************************************

War of Austrian Succession (1740 – 1748)

This raged from 1740 until 1748, and throughout this time Letters of Marque were issued to merchants wishing to engage enemy shipping.

We know that after marrying Mary Bulkely in 1736, FW went off to Italy and based

himself there for the next twenty years or so, engaging in trade and later privateering

-

FW soon became a figure of controversy. In 1742 he was challenged at the gates of the city of Lucca (near Pisa in Northern Italy) and was ordered to give up his weapons. He refused and held a pistol to the head of one of the guards. Another 30 soldiers arrived and restrained him, and was arrested and held prisoner in his Inn for 3 days. Although he was eventually let off, he was forbidden to return. He moved to Leghorn.

Leghorn Leghorn (or Livorno) is in Tuscany, a province of northern Italy. In the mid eighteenth century Austria was the dominant foreign power in Italy and Leghorn was supposedly a neutral port where merchants from all countries could trade and refit their vessels etc. There was a large English ‘colony’ based in Leghorn, and it was these merchants that paid for the fitting out of a privateer vessel for FW.

Contemporary map showing Leghorn (Livorno)

Contemporary map showing mole and fortress

Leghorn today, showing the mole and/or fortress

War broke out in France in 1744 and the merchants of Leghorn suffered from the depredations of French privateers. In 1744 FW’s trading ship SWALLOW was captured by French privateer BEGONIA whilst on trading voyage Lisbon to London, and the captain, William Hutchinson ransomed. As a result of this, possibly in revenge, FW fitted out a brigantine, FAME to ‘cruise against the enemies of Great Britain’ – paid for by the merchants of Leghorn.

In November 1746 FAME engaged two French ships off of Messina (NE corner of Sicily),

one of which ran itself aground in an attempt to escape being taken as prize. The

crew watched helplessly from the shore as FW refloated the boat using rowing-

By the end of December, FAME had taken no less than sixteen French ships as prizes in the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean) with a value in those days of £400,000 (four hundred thousand pounds). One of these had been a French privateer with 20 guns and 150 men, especially fitted out to take FW!

******************************

The Tactics that FW employed

What made FW so successful? Hutchinson describes in his book ‘Treatise on Seamanship’ some of the tactics that had been worked out to maximize the advantages of the privateer.

It must be remembered that the idea was to capture the enemy ship, not to sink it. Often the privateers were smaller than the merchants they attacked, but this gave them the advantage of much greater speed and manoeuvrability. It also made them look deceptively weak, and thus an element of surprise could be used.

When the privateers first went to sea, often with a crew hastily assembled from a mixture of nationalities, it was important to practice both seamanship (so the crew could respond to orders automatically in the heat of battle) and gunmanship. The gunners would often practice on a target such as a floating barrel, and learn to fire as the ship rolled in the swell. By careful timing, they could either shoot across the decks (using canister – musket balls, or iron bars to maximum effect against rigging and sailors) or fire 12lb balls just below the water line, penetrating the hulls and disabling the ship.

Ideally, the privateer would race up behind the prize and swing across the stern as closely as it could, aiming along the length of the deck and, even better, destroying the rudder and steering mechanisms, and rendering the prize immobile. This was usually enough to cause the prize to strike colours.

On December 19th 1746, FW aboard FAME took an exceptionally good prize -

Only two months later, in February 1747, FAME took Turkish property from the French

ship Hermione, bound for Marseilles. It was common for even English merchants to

use French ships to transport their goods (if no other vessel was available) in the

knowledge that if they were captured (by English privateers) the cargo would be protected

by a licence (laissez-

Orders came from Britain to arrest and detain FW, but he was clapped in prison (Leghorn Fortress) by the Tuscan authorities for six months while attorneys fought over the legality of the prize. They refused to hand him over, but he was eventually released, either because the War of Austrian Succession was nearly over or possibly on orders direct from Vienna. Either way, the money was never repaid.

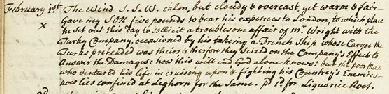

(There is a reference to this incident in the diary of February 1st 1747)

Diary entry for February 1st 1747

Bulkeley gave his son, a lawyer, £5.00 to …

'bear his expenses in London, to which place he set out this day to solicit a troublesome affair of Mr. Wright with the Turkey Company, occasioned by his taking a French ship whose cargoe the Turks pretended was theirs … how this will end God alone knows , but the poor man who ventured his life in cruising upon and fighting his Countrey’s Enemies now lies confined at Leghorn.’

*************************************

SEVEN YEARS’ WAR (1756 – 1763)

In 1755 the war with France was renewed, leading into the Seven Years’ War in 1756. This provided another opportunity for FW to take up privateering again, but his reputation had preceded him and he was in trouble even before setting sail.

He had set up the ST GEORGE at Leghorn (with the intention of privateering) but the Tuscany authorities (supposedly neutral) sided with France (whom they expected to win!) and restricted him to four small guns and only 25 men, the normal arrangement for a merchant vessel. FW took care to ensure that the authorities monitored his work, and requested certificates to be issued to confirm that he had complied with their demands.

FW was aware that, because of his reputation, a handsome price had been put on his

head (Louis XV, the French King, had offered a knighthood and a state pension for

his capture or death. The Marseilles Chamber of Commerce had offered money equivalent

to double the value of FW’s ship). At the same time, a French xebec, a man-

On July 28th, 1756, FW set off escorting 4 English merchant ships laden with valuable cargoes, from Leghorn to London. Being so intent on watching FW, the authorities had not noticed guns, howitzers, handspikes and men being smuggled aboard the merchant ships. Outside of the harbour limits, FW transferred 12 more carriage guns and a further 55 men (a motley crew consisting of Slavonians, Swiss, Venetians, Italians and a few English) from the other ships onto the ST GEORGE.

At 8am the xebec bore down confidently on FW expecting an easy victory – intelligence had told them that the ST GEORGE was only lightly armed. FW ordered the other merchants to bolt and engaged the enemy. The engagement started at midday and lasted 3 or 4 hours. During this time, a lucky shot took away the prow of the French ship, along with the 30 marines preparing to board the ST GEORGE, and altogether 80 men were killed on the xebec with 70 wounded, including the captain and two lieutenants. The ST GEORGE escaped with only light casualties – one lieutenant and 4 men dead, and only 8 wounded. The crew had fought ferociously under the leadership of FW.

After the fierce engagement, the badly damaged xebec was rowed off (its sails were in shreds) and would have been pursued by FW had not another 2 French privateers arrived on the scene. FW regrouped the merchants and took them back to safety – they rewarded him with £120, but the Tuscans were furious with FW for breaking the agreement. (He argued that he had complied with the requests whilst in harbour, that the engagement took place 12 miles off, that it was the Frenchman who was the aggressor, that he was holding the King’s commission (Letter of Marque) and flying under a British flag – and that they had no business giving him orders!).

However, two snows (snoos) anchored alongside with orders to shoot him out of the

water if he didn’t comply, and FW was detained whilst a legal wrangle raged between

Sir Horace Mann, the British Resident at Florence, capital of Tuscany, and the Tuscan

authorities. The governor of Leghorn accused FW or deceit. Eventually, Admiral

Sir Edward Hawke, naval Commander-

On September 23rd 1756 when FW sailed off with merchant shipping (under cover of

the men-

On November 19th 1756 FW engaged two French men-

Unfortunately, Malta was just as prejudiced as Leghorn, and FW was not allowed to

re-

On the 22nd he set off again, but without provisions, and was followed by a large enemy privateer, a French cruiser of 38 guns and 300 men. FW taunted them by sailing around them at twice their speed and shooting at the rigging.

Reports of December 1756 indicate that FW took two other French prizes, the IMMACULATE CONCEPTION and the ESPERANCE, valued at £9000 and £8000 respectively.

By now the King of France was getting very upset at the effect FW was having on French merchant shipping. He ordered the fitting out of two ships with the express intention of ‘burning’ FW at sea. The Chamber of Commerce of Marseilles also fitted out a privateer, the HIRONDELLE of Toulon (a polacca – three masts like a xebec but the main mast square rigged) of 26 guns and 283 men.

There were two engagements of 3hrs in the channel of Malta, and despite the inequalities

of size and armament etc. HIRONDELLE was forced to back off. Both ships put into

Malta for repairs but FW was not allowed to heave out to repair canon holes below

the water line. He was also denied fresh water etc. Because two escaped slaves

had taken refuge on his ship, he was again detained in port until he agreed to their

release. Fortunately, Sir Horace Mann had been working to ease relations with the

Maltese (trade had been affected) and FW was allowed to send his prizes to Leghorn.

Mann wrote him to say that he could return safely-

He was released from Malta and sailed for Leghorn, but was lost at sea with all hands during a storm.

Fe’i rhyddhawyd o Falta a hwyliodd i Leghorn ond fei’ collwyd ef a’i griw i gyd mewn storm.

16th March 1757 ST GEORGE lost with all men at sea. (Adroddiad papur newydd ar Fai 19eg 1757)

***********************************

The following items are in the possession of the Grove-

******************************

Finally

We should go back to 1746 and relate one last anecdote that is so typical of the

character FW was. A French vessel, double the size of FAME had been sent into Malta

to hunt him down. Huge crowds of French sympathisers lined the coast as the two

ships reappeared after a noisy and furious engagement. The French vessel was seen

to be towing the badly damaged FAME, and as they rounded the headland the French

flag was raised on the leading ship. A great cheer went up from the French -

******************************

James Joyce: Finnegan’s Wake

‘… our dollimonde sees the phantom shape of Mr Fortunatus Wright since winksome Miss Bulkeley made loe to her wrecker and he took her to be a rover.’

On his father’s tombstone in St.Peters’ Church, Liverpool is included the following inscription:

‘Fortunatus Wright, his son, was always victorious and humane to the vanquished. He was a constant terror to the enemies of his King and country.’

******************************

In 1748, with the war over, Mary sailed from Liverpool to join FW Leghorn

Fortunatus Wright’s sword

Portrait of Anna, daughter of Mary and Fortunatus Wright

Oil painting of the Fame – a present from Fortunatus to his father-

Fortunatus Wright was the most famous British privateer commander and Liverpool’s favourite hero during the first half of the eighteenth century. His exploits against the French during the War of Austrian Succession and later at the start of the Seven Years War would rival any adventure of Drake or Raleigh, and yet he is largely forgotten nowadays. He was a colourful mixture of rogue and swashbuckling hero, by all accounts a likeable villain.

We know that his father was a mariner – Captain John Wright – and that he died in

1717, because of a gravestone is in St. Peter’s churchyard in Liverpool. The gravestone

also records that the Captain “gallantly defended his ship for several hours against

two vessels of superior force”. We don’t know very much about the early life of Fortunatus,

except that he born in 1712 and became a brewer in Liverpool. We assume he learnt

his sea-