Cymdeithas Hanes Mechell

The Demography of Llanfechell 1851 & 1901

William Bulkeley and the poor of Llanfechell

Llanfechell in the early 19th Century

*******************************************************

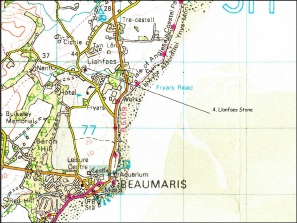

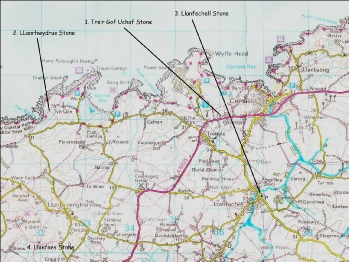

The information has been arranged in four sections, namely the story of the four stones.

Click on pictures to see larger versions

*******************************************************

The Tre'r Gof Uchaf Stone

This stone has been placed in the wall in front of the house.

On the second picture and the third, which is a rubbing, we can see the initials

of Richard Broadhead and his wife, Martha. (She was Williams, the daughter of Pensarn,

Llanfechell). She had aunts and an uncle who lived in Neuadd, Cemlyn; he was the

priest at Llanfflewyn. The significance of 1773 is probably the date when the couple

returned from their place at Bodorgan to Cemaes. There is extant a description of

the two, ‘He, a handsome, auburn haired man, dressed in a blue, cut-

Richard was the son of William and Catherine Broadhead of Cromlech. Catherine had

been house-

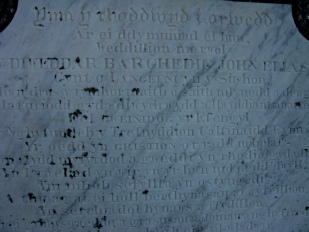

The photographs show the graves of Richard and Martha in Llanbadrig. His tombstone is found leaning against the wall on the left, on entering the Church. Martha’s tomb lies alongside the Church wall outside, its railings corroded. One can just about read her name, Martha on the tombstone.

Richard's tombstone

Martha's tomb

Martha's tombstone

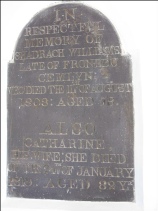

A memorial to Shadrach and Catherine Williams

Inside Llanrhwydrus Church one finds a memorial to Shadrach and Catherine Williams. She was Catherine Broadhead, sister of Richard, and Elizabeth Broadhead’s aunt. Shadrach has been described as ‘an owner of ships, and a great improver’. He lived in the ‘Fronddu’ and he owned the Storehouse on Cemlyn point where he had been given a lease for so many lives by Owen Putland Meyrick. Here, oats bought from local farmers were exported, and coal from Flint, and salt from Liverpool, were imported.

John Elias’ son says in his memoirs-

‘There is a building comprising storehouses, built specifically to store the oats bought locally, with a dwelling built on one end for a family, and to supervise the oats, because the place was so remote. There is also a large yard to sell coal, because Providence had made there a natural harbour. The Fronddu family had bought thousands of pecks of oats; and the seller had never any qualms but that he would receive payment for each grain. Everyone was happy, on threshing his corn, to take it to Cemlyn.’

The Fronddu family were ardent Methodists, and the often invited itinerant preachers to preach at their house.

Shadrach had also been given a lease by Lord Bulkeley to build a stone house in Llanfechell Square. The date of the indenture is 12th November, 1776

‘Erect building Compleat (sic) and finished in a workmanlike manner with suitable lime, morter (sic), a good stone house of Dimensions and to be filled and made up in manner hereinafter mentioned etc.’

BShadrach intended that one of his children should live here, but when Elizabeth Broadhead’s parents, and also her family at Neuadd, Cemlyn, heard that she had been to a certain Methodist’s house and that she also attended meetings at Fronddu, she was disowned, and as a result was allowed to use half of Shadrach’s new house at Llanfechell, to keep a shop. On marrying, she was given the whole house.

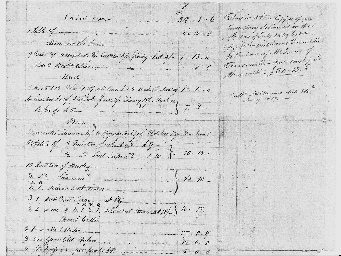

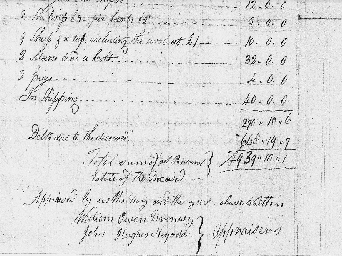

It is of interest to see the value of Shadrach’s business on Cemlyn point and the

farm at Fronddu. Here is a copy of Catherine’s will worth about £1000, including

money owing to her (Shadrach died before her) because Shadrach was also a money lender.

John Elias had borrowed £200 on behalf of his fellow-

Catherine’s will

*******************************************************

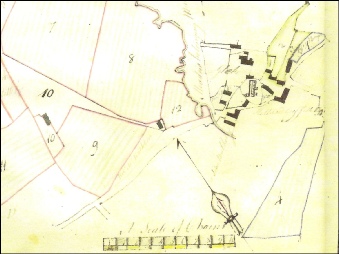

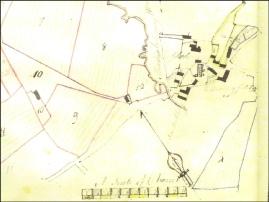

Map of Llanfechell 1805

Map of Llanfechell 1865

John Elias was married in 1799, and John, his son, born in 1800, so the 1805 map is entirely relevant to the story.

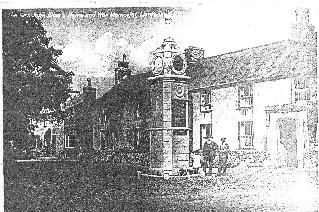

Where the cross stood

The son wrote his memoirs a year before he died, in 1875, where he recalls the Llanfechell of his childhood.

‘There is a fairly high rock, which then had a cross on top, and (in the past) there were benches of stone surrounding it, on which the vendors in the Market sat, and placed their baskets and sacks. There was below the rock a flat area for their use. The place is still called Penygroes. The cross’ shaft is now in front of Bodelwyn, a farmhouse near the village. I do not know why it was moved there.’

Where the cross stood is where early Methodist preachers used to preach, where Peter Williams, the publisher of the famous edition of the Welsh Bible once stood. Penygroes, the house, was built by the master carpenter William Parry, a Methodist, who incorporated the stones on which Peter Williams had stood, into the house. William Parry trained many apprentices, who in their turn left for Liverpool. One of them, Owen Elias, of Creigiau, Llanbadrig, known as the ‘King of Everton’, became a master builder and a devoted Methodist deacon in that city.

Some say that Penygroes was once called Bryn Y Groes.

The arm piece of the cross is now in the burial ground of Llanfechell Church immediately

on the right, on entering the gate, and there was once a sun-

Map of Llanfechell 1805

Map of Lanfechell 1865

Where the houses once stood

On the map of 1805 there were three houses near the church. The first would have been immediately on the right on coming out through the church gate. Here lived Jane Owen Edwards, in a small thatched cottage, with just enough room for a bed which reached the door. It contained only a round table; a spinning wheel; a stool (no chair), one shelf, a plate, a bowl, and one spoon. Jane was slovenly and used snuff, and she worked every day at her spinning wheel making packing thread for Elizabeth Broadhead’s shop. What is remarkable about this woman is that she walked all the way each Sunday to join the Congregationalists at Amlwch Port.

The next house had a loft – the house of the tailor, William Owen. Both he and his

wife were clean and tidy, William, unlike his neighbours, could speak and write English.

He did some work for Elizabeth off and on. He boasted, proudly a certain type of

watch ‘ Fletcher-

The third house was called the old Meat Hall, harking back to the days when there was a market at Llanfechell, before the Parys Copper Mines were opened. Here, Hugh Pritchard, labourer, lived, a hard and honest worker who had married the tailor’s daughter next door. John Elias’ son says that Hugh and his wife had many children, one about the same age as John, and John says ‘it was beneficial for me to have been raised up on this woman’s milk’

On the 1865 map they are not there. There had been a dispute between the parishioners

and the church as to the ownership of this land, where the houses’ gardens extended

towards the churchyard. Apparently, the church won the argument-

The Post Office as we know it today was called Hen Siop in those times. Here, the carpenter William Parry adapted the empty loft into a chapel, where John Elias and others preached, and where a successful Sunday School was built, Here too lived a woman who sold sickles by the dozen provided by her family from Lleyn. John Elias’ son remarks that the scythe was not in use at that time.

Licence for Ale House

Nearby was Plas, where the Breretons lived. The eldest Brereton was a scholar, who could prepare wills and deeds that no solicitor could find fault with. He also kept a school. There was also a brewery and stables for travellers’ horses.

A girl from Plas married an Owen Jones, Ty Mawr, Amlwch, who came to live in Llanfechell.

Their son was called Andrew Bereton Jones, of whom we shall hear more, and he was

taught, together with John Elias’ son, John by his grandfather. John Elias junior

relates an incident that took place at this time-

‘‘A genial spinster, named Margaret Williams, lived with her father in an old house,

just alongside the church, and one day instead of going to school, I stayed there.

When the children came out, I joined them, humming to myself but my father had seen

me leaving Margaret Wiliams’ house. There I was, being conducted homewards, to face

the judge, and the verdict? Imprisonment! The prison was the little parlour, with

my feet tied in a sheep’s fetters. I was to be given no bread or water, so it was

worse than the jail at Beaumaris. But little John Elias was not to be left unfed

even then. Mary Jones of Bwlch, came to the village, heard about it, and in a house

in the village, she had bread and butter, and I think there was sugar on it as well,

and on opening the window, she pushed me the timely and pleasurable gift. There was,

I expect, no clause in the little parlour regime that disallowed the opening of a

window, and it is not easy, anyway, to form a law which has no loop-

Tan Y Fynwent

The next house of interest to our story is Tan Y Fynwent where Robert Edwards ,

the blacksmith lived, the man who shoed John Elias’ horses, and who always gave preference

to the preacher, because he knew about his long and incessant journeys, journeys

which had many hazards, as this incident reported in one of his biographies-

‘We are told of an incident that took place when he was crossing the Menai Straits from Anglesey, at Moel y Don. The horse he had with him on the ferry was a particularly nervous creature, and before they sailed, he asked the boatman not to raise the sail incase they unsettled the horse, and, so endanger all their lives. Yet, in spite of this, after they had left the shore, the sail was raised; the animal took fright, and leapt out of the boat, into the sea, pushing Mr Elias into the water! One of the ferrymen jumped in after him, but Mr Elias came to the surface, and swam easily on his back, and he was gradually lifted back on to the ferry. He and his horse crossed without any further mishaps or scrapes. It was reported that he preached powerfully that night at Carnarfon.’

Siop Newydd had a space once before it, before Penygroes was built, where the early Methodists used to preach

Siop Newydd

Y SIOP FAWR!

The most important house for our story was Y Siop Fawr, home of John Elias.

John Elias' home and War Memorial, Llanfechell

There were five important individuals of the many who came to the Siop Fawr-

1 Rees Jones

He was a blacksmith. His forge stood where Cemlyn Chapel is now. He taught himself theology, with John Elias’s help and he often visited Y Siop Fawr where he was also helped to master English with Elizabeth’s help. It is a testimony to his strength of character and determination that through John Elias’ recommendation he became Minister at Penclawdd, the Gower Peninsula.

Tŷ Capel Cemlyn

2. Captain Thomas Owen

He became a Methodist and worshipped, with John Elias but he back sided and renounced his faith. It is possible that he married one of Shadrach Williams’ family. He and his ship and crew were taken prisoners by the French during the Napoleonic Wars, and the men were sent to Verdun. John Elias wrote him letters and collected money for his wants, which were sent via an agency in Paris. After the war, he returned to Cemlyn, but died young from the effects of his privations.

Thomas Owen's tombstone

3 Andrew Brereton, Plas.

He was apprenticed in the Siop Fawr after attending school under John Owen in a schoolhouse

which William Parry built (where Libanus is now). He eventually left for Liverpool,

and then Mold, where he owned a large brewery. He was a poet and a prose-

‘The beautiful maid, Nelly-

Elias of Wales

Godliness, and sincerity

Shone always on her dear face’.

Andrew returned to Llanfechell in 1877, to adjudicate some of the poetry in the Anglesey Eisteddfod held there. He also donated money for a scholarship to Aberystwyth University.

Plas, Llanfechell

4. Thomas Lewis

From Tyddyn Gyrfa, Cemaes, schooled at Llanfechell. He was apprenticed by Elizabeth

Elias in Y Siop Fawr. He became a very wealthy flour dealer in Bangor and travelled

the world extensively earning for himself the title Thomas Palestine Lewis (1886-

Thomas Lewis

5. Hugh Jones

He, too, was apprenticed at Y Siop Fawr, under John Elias’ son. He became the Rev.

Hugh Jones of Liverpool and is remembered for his biography of the Rev. William Roberts,

Amlwch, Saunders Lewis’ great-

Hugh Jones

John Elias in Llanfechell

It was through a twist of fate that John Elias came to Anglesey, sent as a last minute

replacement from the training school at Caernarfon. Somehow, later, both he and Elizabeth

Broadhead met and were married, in Llanfechell Church by the Curate John Jenkins.

His friend, Richard Jones, from Eifionydd, was best man, and Richard preached outside

Y Siop Fawr-

Llanfechell Church

Of course, they settled in Y Siop Fawr. Her name only was above the door, although

there is a document referring to John as a ‘grocer’. Sometimes he helped to tidy

up the shelves, but spent most of the time in his study, reading mainly the Puritan

writers. From London he once wrote-

‘After long waiting for that Laceman from Northhampton, and waiting in vain – today I took Mrs. Davies my Land Lady with me who is a good judge of such things, we went to the cheapest place that we could find in London and I bought worth £8:4:4 of the best Laces and the best patern according to our fancies and I think them very good for the prices.

I will buy the worth of the remainder of the money before my Departure from here. I have kept some money in hand on purpose to expect that Lace Man from the country.

I will send the Laces, in a small parcel with the Mail tonight to Mr. Owen Holyhead and I’ll pay the carriage here.’

From the start John Elias had two important friends, who shared with him some very

exceptional life experiences. There was Richard Lloyd of Beaumaris-

The other friend was William Roberts of Amlwch, another Methodist Minister who kept

a shop with his wife in Amlwch Port. William Roberts suffered a deep depression,

when he, like Elizabeth Elias, invested capital for wares for their shops, but lost

everything when the Marchioness of Anglesey ran against Ynys Dulas in a storm...

The newly-

The story of how William won ‘his new and gentle partner’ is one of the most romantic (like John Elias really). William courted Sarah Jones, the daughter of a large farm, Gwern Hywel, in Denbighshire, but his family adamantly opposed a marriage. Moreover, early one morning, Sarah climbed out of a window, into her lover’s arms, and was carried on horseback to Llanfechell, where they were welcomed by John and Elizabeth Elias.

Elizabeth Elias was a courageous and selfless woman who allowed John Elias to devote his life to preaching without having the cares of running a shop and raising a family. She had four children, John, Phoebe, and two others, who died in infancy. Her son writes somewhere ‘my mother struggled constantly against the tribulations of this world, with very little to support her.’ The loss of the Marchioness of Anglesey had been a terrible blow.

Even so, Elizabeth went all the way to chapel at Llanrhuddlad on Sundays, where old

Evan Thomas, the famous bone-

After John had left Llanfechell to a school in Abergele, and then in Chester-

The father appeals for his mother’s sake-

He praises Phoebe, his sister, how well she is coping. ‘It is not over-

The truth was, the business had been thriving for years, and Elizabeth could retire.

He tempts his son, ‘We have a new van, very fine-

John came home! Also because John was in-

Elizabeth Elias died in 1828, aged 59, six or seven years after John returned home.

The business flourished even more, as a bank book of John’s shows. Two years after

the death of his wife John Elias had re-

He had known his new wife for some years, Ann Bulkeley as she was, by now, an ordinary

girl from Aberffraw, who had been a maid at Presaddfed, Bodedern but had married

Sir John Bulkeley, who died. Letters written by his children from his first marriage

show how the family discussed ‘ how to get the little lady’, especially those by

Margaret Emma, wife of James King, the Master of Ceremonies at Bath. Ann left Presaddfed

having been allowed the means to live comfortably for the rest of her life. She and

John Elias renewed their acquaintanceship in Dronwy, Llanfechell. The couple were

married in Liverpool, from where John Elias wrote this letter to his shocked children

(and rebellious daughter, Phoebe-

February 18. 1830

Dear Son,

I feel restless from the need to write to you and your sister, and I should be so relieved to hear from you. I can think of no better means than to hear that you are both well and prospering. I would write to both of you together, if I knew that my dear daughter, Phoebe, could wish and tolerate it. A change in my situation does not change my relationship with you nor of my concern for both of you. Perhaps you find it difficult to believe this now. But I am writing in the presence of He who knows the secrets of the human heart. One day you will discover that I speak the truth. Your needs and your happiness, temporal and spiritual, are very near to my heart. I still do not think that we have displeased God in this change of circumstances.

John Elias took legal steps to hand over the shop and possessions to his children. He also wrote a conciliatory letter to his old friend, Richard Lloyd.

Phoebe’s fate is another story. So is John’s to a certain extent. Their father and their step mother set up house in y Fron, a large house in Llangefni. There came a day when John, at any rate, was able to receive a visit from his father and new wife, and one can only feel that Ann’s personality seems to have mollified John’s rancour.

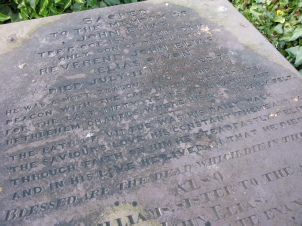

Elizabeth's grave, Llanfechell Church

John Elias Junior's tombstone, Llanfechell Church

*******************************************************

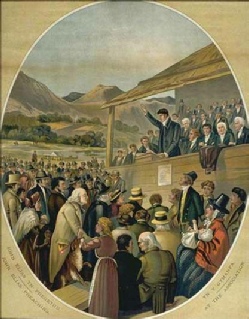

Once, a Methodist deacon from Llanfechell, Robert Williams who had known John Elias, was asked by a young preacher whether John Elias would have had the enormous effect if he was alive that day. His reply was, ‘young man, John Elias could stir a congregation by removing his hat more than any preacher today could with his best sermon.’

And that is the way of it! We have no means of knowing what he was like, only through

the words of his contemporaries. After all, there were no recordings; we depend on

the words of those who had heard him. There was no camera, only an artist’s impression

of him. True, he left over two thousand sermons, but they are not the same. He is

not here to utter them – although they can give us some idea. But what strikes us

today is, if we read the words of his contemporaries, how, if we take a wide spectrum

of witnesses, they all agree as regards his great gift. One minister says ‘John Elias

is acknowledged to be the foremost orator of Wales’. One unknown writer in ‘Y Drysorfa’

says-

‘After the storm of thunder and lightning fell the refreshing rain; the clouds cleared; the sky brightened; and the sun of grace and justice shone in all its power on all souls.’

And today the new Welsh Encyclopaedia calls him ‘the most powerful preacher of his day.’

John Elias

He must have had an astonishing presence. He stood only five foot ten inches tall

in the pulpit, but he was always absolutely straight until his emotion made him lean

forward. He was also thin. When young, he had stood before a mirror to practice using

one of his fingers effectively. But this was not mere histrionics. All people acknowledged

his sincerity. And he had been gifted with a powerful voice, a voice that, according

to many witnesses, could make hardened men sway before him like the waves of the

sea. And he was always in control of his emotions, of each sentence and paragraph-

He was accused of being an extreme Calvinist, the belief that some were saved predestinally, and that it was useless to preach to the unsaved! He never delivered a sermon without making it absolutely clear that everyone had a way out of his dilemma.

He advised his son-

‘ Wait on God ……. Stretch out your hand, although it

is withered, arise, like the prodigal son, although in a foreign land, and dying

of privation;-

The late Dr R Tudur Jones was undoubtedly the world authority on the early Puritans,

in whose tradition John Elias stood. He wrote-

‘Elias took man’s crisis seriously. To people in the grips of alcoholism, bestiality, aggressive lust or the crisis of the meaningless of life, it was a great joy to listen to a man who took their difficulties seriously. Nothing deepens people’s anguish more than to listen to religious leaders treating their condition like a joke’.

His, John Elias’ influence, was great, here in Anglesey, where he thundered about

breaking the Sabbath; against working the mills on a Sunday, against performing interludes,

or plunder shipwrecks. He had much of his own way in the Societies and Assemblies,

and left his mark on the Methodist Declaration of Faith. He was against the Reform

Act of 1832, an act which increased suffrage from 435 to 653 thousand, and he condemned

any Methodist who took part on a political stage. As a Tory, he endeavoured to hold

back the incoming sea of radicalism, and succeeded to a great degree-

He opposed Catholic Emancipation when Daniel O’Connell’s great rallies stirred Ireland. When he heard that a number of young men who were members of Jewin Chapel, London, had written an Address to Parliament, supporting emancipation, John Elias was furious. He was called the Pope of Anglesey, the old Jim Crow in his tall, black hat. He insisted that these men were expelled from the Connexion, among them Arfonwyson, who worked in the Greenwich Observatory, and Caerfallwch, the Lexicographer

One explanation for his Toryism is no doubt, his early experiences, when he and Richard Lloyd were accused of treason.

He still loved the Church too in his heart. He did, however, oppose slavery, and wrote letters to churches in Liverpool, where members worked at making fetters and chains, instructing that those workers be expelled.

If many people wished to see the back of Elias, they would soon have their wish. He and a friend in the Bala region, were thrown out of a carriage when the horse was frightened by two boys, and bolted. One of the shafts snapped, and Elias was thrown out, and landed on his head, and injured his foot... He was never entirely well after this incident, and in time had to rest more, until he was confined to bed suffering from gangrene, from which he died in 1841

Llanfaes Church

His tombstone

John Elias' grave

We are left with the memory of a great talent. In the words of Dr R Tudur Jones-

‘He had the oratorical gift to convert strong feeling into a crystalline prism, through which one can find truths, in a way that the truths are everything and medium nothing. This is the secret of all the greatest orators in the world in every age.’

He had wished to be buried alongside his old friend, Richard Lloyd. On the day of his funeral, the cortège started from Y Fron, Llangefni, for Llanfaes, a distance of twelve miles. Before the coffin, rode a number of carriages carrying ministers and doctors; then behind the hearse, carriages carrying the family. Afterwards, forty ministers riding in twos; followed by about forty carriages. Then one hundred and fifty horse riders in twos; and a huge throng walking in fours. The procession was very long, and by the time they reached Beaumaris, it was a mile and a half long. It was estimated that 10 000 people had joined the cortege.

In the phraseology of the those times, it was in this way that the great man of Israel went to his everlasting home.

*******************************************************

Thanks to Mr Mike Harris for his help with the photography and to Mr Robin Grove White, Brynddu, for the 1805 and 1865 maps of Llanfechell.

The old shop

Plas

with thanks to Mr Glyndwr Thomas

Llanrhwydrus Church

Penygroes

The arm piece of the cross

John Elias' son